Edvard Munch’s German Letters

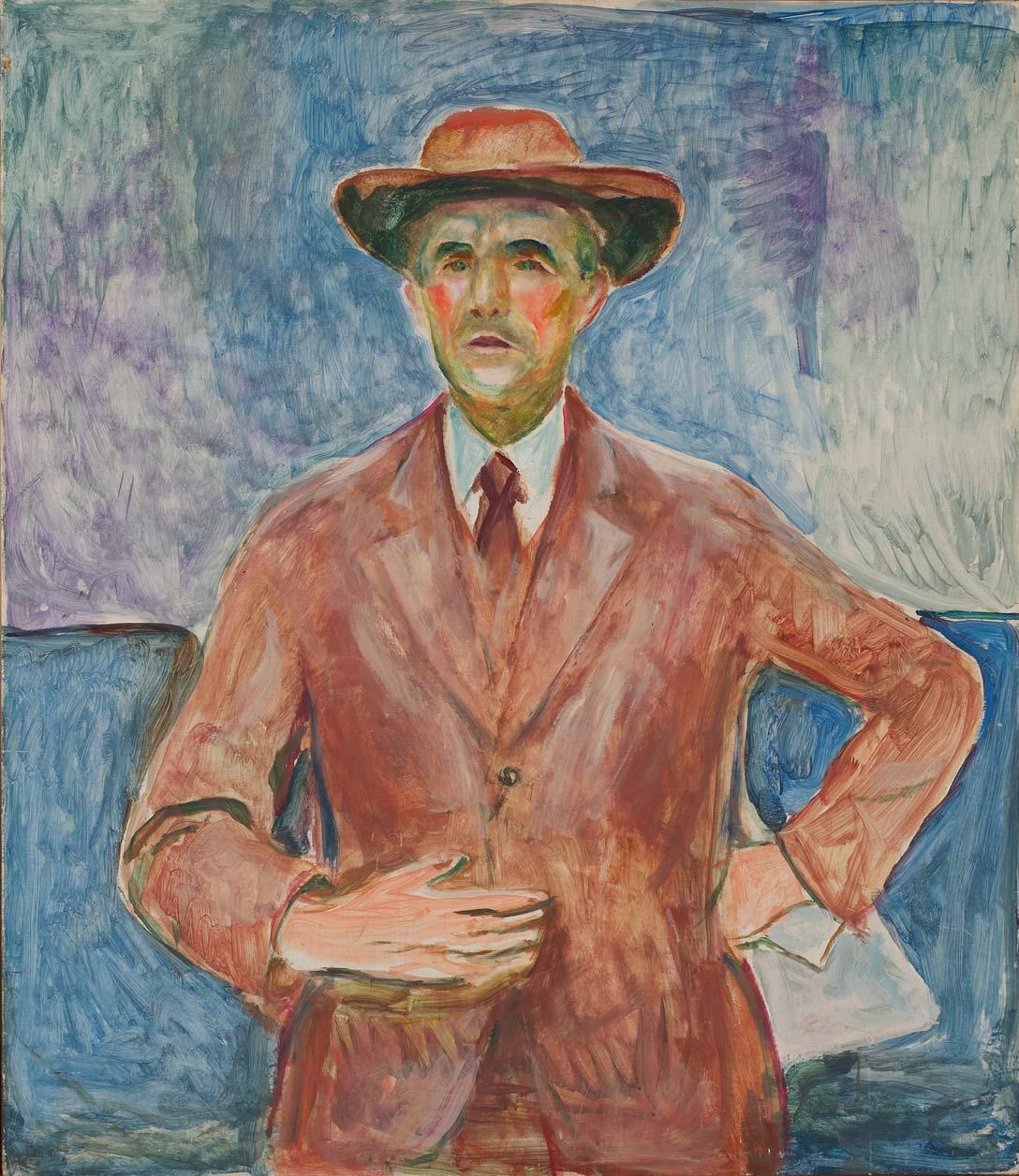

CAT. 42. EBERHARD GRISEBACH 1932

Munch’s relationship to Germany gained momentum in earnest in the fall of 1892 after the scandal exhibition in Verein Berliner Künstler. It was from that time onward that he became acquainted with German artists, and also writers, such as Richard Dehmel (1863–1920), who was considered one of the most important German poets of his time. Aside from personal encounters, a correspondence developed between Munch and colleagues, art dealers, patrons and others, and he was thus forced to write in German. The letters bear witness to the fact that he was quite unschooled in German, and the extent to which he mastered it at all was rather verbal. His German letters give us a glimpse of a situation where the painter feels hampered by the language, but nevertheless – because he has to – develops a language that serves his aim surprisingly well. Examples of this “Munch-styled” German follow in this article, but first a few words about the extent of his knowledge of German before he was forced to actively learn the language.

Where Munch Learned German

It is believed that Edvard Munch’s schooling began with his father’s private tutoring. His aunt and siblings may have also contributed. In any event, his first classroom instruction was at Gjertsen’s School of Higher General Education, where he began in the second year of middle school in the fall of 1874. It was a time, as Erik Mørstad writes, when “German and English won precedence over Latin as foreign languages” in the educational system.1 According to the curriculum, Munch had five hours of German instruction per week during the months that he attended this private school. In 1875 he enrolled in Christiania Cathedral School in the third year of middle school. Here too German was part of the curriculum, but he left after only a few months, and little is known about what kind of private tutoring he subsequently received, from 1875–79. In all, he had completed the equivalent of one full year of schooling by the time he was 15.2 In 1879 he enrolled in Christiania Technical College, where liberal courses must have been included in the curriculum. In the entry for 25 August, Munch writes in his journal that he has taken his oral exams in mathematics, history, geography, English and German. “I was a bit nervous Because of my Lack of Familiarity with the examination process but I think that I did tolerably well.”3 But from that time on, his education became specialised, and – as Mørstad writes – he exclusively attended drawing classes at Christiania Technical College and later at The Royal School of Design.4

In others words, Munch gained a fundamental introduction to German in his early years, but a real, closer knowledge of practical German did not come until later, during his sojourns in Germany and via the correspondence that became necessary for his artistic career.

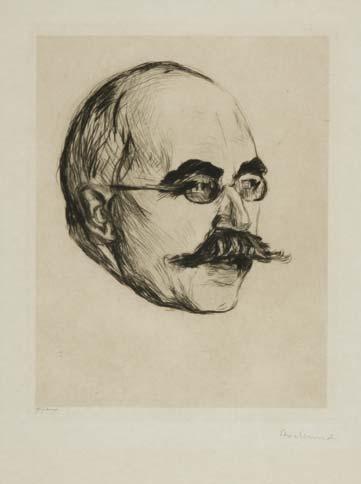

CAT. 73. GUSTAV SCHIEFLER 1905–06

Munch declared repeatedly that he was no letter writer, yet he left behind approx. 1500 German letters (both sent ones and drafts), as well as a few lists of picture titles. Most of these are housed in a number of German institutions, in the Munch Museum and the National Library of Norway in Oslo. Of this material little has been published aside from the important correspondence with Eberhard Grisebach,5 Max Linde6 and Gustav Schiefler.7 The correspondence with Schiefler is particularly important in studying the development of Munch’s German, since it spanned many years, from 1902 to 1935, at which time Schiefler died. (It continued in subsequent years with Schiefler’s family up until Munch’s own death in 1944).

Root German

Signe Bøhn maintains in her introduction to the edition of Munch’s correspondence with Gustav Schiefler that there are a multitude of mistakes in Munch’s letters regarding almost every rule of German grammar and spelling.8 It is a feature that jumps out at you. But at the same time he is shrewdly candid in German: He apologises many times for his language mistakes, yet disguises a good portion of them via a writing style that often leaves the choice undecided between nominative– accusative, genitive–dative, plural–singular. The handwriting also has other inconsistencies. Munch writes the letter ß in different ways, both in keeping with the convention as ss (where the last s is either Latin or the Gothic long s), as sz or incorrectly as zs or simply z. But this is a mere trifle, as is the lack of punctuation. He prefers the use of the dash – or nothing – where he should have placed a period, and the comma is totally outside his sphere of interest.

Many of the more interesting mistakes can be explained as literal translations from Norwegian, such as for example zu Herbst for “this coming fall”, or as here, where the Norwegian syntax leads to the incorrect placement of the verb: “ich habe ofter gedacht an Ihre merkwurdiche Leben da oben auf Davos”.9 Other mistakes have accumulated in this sentence as well; for instance “life” – “Leben” – has lost its neuter gender.

The following sentence is also typical; notice that Munch not only uses Norwegian syntax but also ignores the fact that German is a language that has cases: “Er versteht nicht das mein Kunst kriegt sein Kraft erst in meiner voll Freiheit”.10 Does he also permit himself the freedom to pare German words down to their roots? This is what he does, in fact; periodically writing what we could call “root German”, with a Norwegian sentence structure, and where the roots are allowed to remain as they are, robbed of any morphology.

CAT. 24. MAX LINDE IN SAILING OUTFIT 1904

The lack of diacritical marks is a rather insignificant mistake, but nevertheless presents a challenge in Munch’s German: in many cases a, u and o should have been ä, ü and ö respectively. Even a word like Gemälde [painting] has to manage without a tilde mark in Munch’s writing. These dots are simply beyond him. It generally does not cause a problem in understanding, but this carelessness – or whatever it is – becomes “ratzelhaft”11 [rätselhaft, enigmatic], and a problem, when it comes to verbs. He writes waren, for example, when it should be wären. The mistaken use of the indicative for the subjunctive reveals a lack of understanding of this distinction in German, or perhaps Munch is aware of the category of mood, but is unsure and doesn’t wish to waste time on it, and therefore avoids the whole problem by leaving it to the recipient to guess which tilde mark is missing.12 At other times, he seems not to care in the least what is correct or incorrect and inserts tilde marks quite arbitrarily, as here in a draft of a letter to Max Linde that describes the behaviour of a common acquaintance: “Er macht mir confus zuletzt durch seine Brüllen (ich sage es unter uns das es thatsachlich unverschamt ist diese Brullen)”.13

Is there any trace of a development in Munch’s German letters? At first glance it does not appear so. 16 December 1894 he writes to his sister Inger: “I am a very diligent painter and engraver all day long – I almost never see any countrymen so I will probably learn to speak German well – ”.14 Having managed six months earlier to produce the phrase “von der krank Mädchen”,15 one would have hoped that the months in between had produced results when it came to German morphology, but this was far from the case. Common mistakes, carelessness and grammatical blunders still abound, and will continue to do so throughout all of the German correspondence. In 1902 he begins a letter with a phrase that we can (with a portion of goodwill) read in its correct form: “Mit bestem Dank für Ihren freundlichen Brief”,16 yet five years later he falls back to “Besten Dank fur Ihres Briefes”17 and continues in this vein.18 His vocabulary, idiomatic expressions and grammar do improve over the years, however. Such poor grammatical sentences as the following are found less often from 1910–20’s onwards: “Ich habe zu Sammen ein Skitse gemacht – eine Frau whelche wie eine Wampyr – ein vogelhaftes Geschopf uber ein todte mann schwebt”.19 Yet many of the mistakes and orthography have gained a foothold; the wrong gender in nouns, a lack of or mistakes in inflection endings and writing such as ich wheisz can still be found during the 20s and later. And the tilde marks never gain any place in Munch’s German, although we can see a small tendency towards increased attention to the phenomenon from the 30s and after. Even the author Goethe is equipped with a tilde mark that he had no use for: “Göethe”.20 Perhaps he writes this and similar things while in a state of hyper correctness. Or can it be that Munch had read a good deal more German since the 1890s? The letters prove that he received books from German acquaintances, and the sentences at least become more sophisticated. But he continues to think in Norwegian, as when he agrees to sell Sick Girl and leaves out the article the Germans would expect before the name of the museum that wishes to acquire the painting: “... damit einverstanden bin das Bild krankes Madchen an Dresdener Kunstmuseum zu verkaufen”.21 Prepositions are always difficult in foreign languages, and it is no wonder that in a letter to Frederick Delius about “the transparency of the body” he reminds his friend of how, thirty years earlier, they had spoken not von der, but “um Durchsichtigkeit des Körpers”.22

The Voice in a Foreign Language

Munch can hardly be said to have had a conscious plan for his German orthography or grammar. On the contrary, he wrote in a hurried, busy and forgetful state when it came to what he must have learned in his childhood and youth. But it is also clear that he had learned quite a bit of German in his encounters with Germans. A spelling such as richtich instead of richtig indicates that he had been influenced by the oral language. As is the case when he apologises as follows: “Ich habe alzo kein Geld”,23 but here it is the Norwegian pronunciation that is evident.

We understand that Munch never really applied himself to learn the foreign language when, in the quoted letter to Delius, he apologises for having begun the letter to him in Norwegian, and then remembered that it should have been written in German. We also learn here that he used three weeks to answer letters.24 This is hardly due to the actual writing of them, as they are written in a hasty – at times illegible – tempo, but more likely indicates the interval of time between receiving and answering his mail.

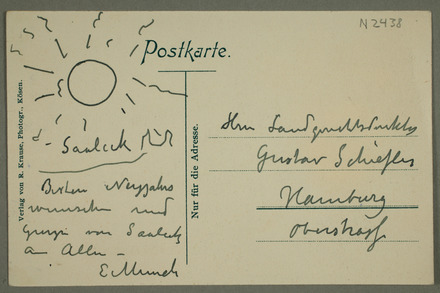

ILL. 8. POSTCARD FROM EDVARD MUNCH TO GUSTAV SCHIEFLER 1906, MM N 2438-1

But is Munch able to express what he wishes? What would the recipient have thought when reading the following: “Ich glaube wir uns einmal unter glucklicher Umstande uns wiedersehen”.25 She would hardly have had problems in deciphering the message; letters usually have a clear context, even though the syntax here is neither good German nor good Norwegian, but rather French inspired (je crois (que) nous nous verrons).26 The prospect of this future meeting taking place is in any case vague; to believe in an encounter in the infinitive is not quite feasible.

The language mistakes were a handicap for Munch, not because he had a problem being understood, but because he was vexed by his lack of skills in this art, and had to struggle to get through the correspondence, as he complained of in a draft of a letter to Nietzsche’s sister: “Wie immer zerreisze ich die Briefe – es ärgert mich die Fehler der Sprache –”.27 He periodically makes efforts to write as correctly as possible; corrections in the text reveal that he has scratched his head and wondered about the case endings. But his attempts at reviewing his school grammar lessons are, if not half-hearted, then at least not indicative of his having used much energy to achieve a higher level of German.

For Munch the German language was a great reservoir of words in their basic form. Adjectives and nouns, and verbs too, are used without being declined or conjugated or incorrectly so, and naturally in many cases also correctly, yet in a way that reveals that he assigns little importance to it. For him communication is not about congruence between subject and verb, about strong or weak declinations of adjectives, but about the adjective, the noun and the verb, pure and simple.

When one can ascertain that Munch had an impressive vocabulary, as Signe Bøhn does,28 one glimpses a strange lopsidedness in his relationship to German. Though he had a poor knowledge of the formal and scholarly terminology, he was nevertheless well-versed in the German vernacular’s expressive possibilities.

Hinrich Schmidt-Henkel warns us against drawing a corollary between Munch’s many drafts of letters, between the unfinished, spontaneous style, the mistakes, etc. and his fluctuating psychological state, which is the subject of many of the German letters.29 I believe Schmidt-Henkel is justified in doing so, for the tendency towards total grammatical chaos and the linguistic spontaneity in the letters say more about the proximity between thought and writing than about Munch’s nerves. I for one am charmed by this language, at times almost a pidgin German: “Vieles schuld ich das kraftige og groszzugige Deutschland –”.30 On the other hand, Munch can also produce perfectly formulated German sentences: “Ich schreibe leider sehr schlecht deutsch – sonst hatte ich mehr geschrieben –”.31 Here he is only a couple of tilde marks (“hätte”) away from transforming his German from being “schlecht” to being perfect.

Like Henrik Ibsen, Munch was for many years considered a German artist, or – to put it another way – part of the Scandinavian sub-division of German art. But contrary to his elder countryman, he was not well-versed in the German language. Yet the considerable mastery of formal business German that Ibsen exhibited, Munch more than matched with his direct style – with many mistakes perhaps, but just the same in a way that conveyed a more personal and creative passion.

Notes

1 Erik Mørstad: “Edvard Munch’s First School Years: Teachers and Textbooks on Drawing” in Munch Becoming ‘Munch’. Artistic Strategies 1880–1892 (exh. cat.), Munch Museum , Oslo 2008:24–5.

2 Mørstad 2008:30.

3 Inger Munch (ed.): Edvard Munchs brev : familien. Oslo: Tanum, 1949:37. Thanks to Åshild Haugsland for the reference.

4 Mørstad 2008:30.

5 Lothar Grisebach (ed.): Von Munch bis Kirchner : Erlebte Kunstgeschichte in Briefen aus dem Nachlass Eberhard Grisebach. Munich: List, 1968. New edition ed. by Lucius Grisebach: “Ich bin den friedlichen Bürgern zu modern” : aus Eberhard Grisebachs Briefwechsel mit seinen Malerfreunden / herausgegeben von Kirchner Museum Davos; zusammengestellt von Lothar Grisebach ; überarbeitet und neu kommentiert von Lucius Grisebach. [Zurich] : Scheidegger & Spiess, 2010.

6 Lindtke, Gustav (ed.): Edvard Munch – Dr. Max Linde : Briefwechsel 1902–1928. Lübeck: Senat der Hansestadt Lübeck, Amt für Kultur, 1974.

7 Arne Eggum (ed.): Edvard Munch / Gustav Schiefler. Briefwechsel. Verein für Hamburgische Geschichte, Hamburg 1987, Vol. 1:29–32. (= Veröffentlichungen des Vereins für hamburgische Geschichte, Vol. XXX).

8 Signe Bøhn: “Edvard Munch und die deutsche Sprache” in Arne Eggum (ed.) Edvard Munch / Gustav Schiefler. Briefwechsel. 1987: 29.

9 Letter to Eberhard Grisebach 17 July 1909, eMunch.no: PN 103.

10 Draft of a letter to Max Linde (c 1902–3), MM N 2333, Munch Museum.

11 Draft of a letter, MM N 2366, Munch Museum.

12 The publishers of the Munch-Schiefler correspondence (Eggum (ed.) 1987) added the missing vowel mutation marks (cf. Vol. I:34 and Vol. II:25). The obscurities in Munch’s language were thus covered up to increase readability.

13 Draft of a letter to Max Linde 1902, MM N 2319, Munch Museum.

14 Inger Munch (ed.) 1949:148. Thanks to Åshild Haugsland for the reference.

15 Draft of a letter to Meier-Graefe, 26 June 1897, MM N 2353, Munch Museum.

16 Letter to Ernst Rose 1902, eMunch.no: PN 933.

17 Letter to Albert Kollmann 1907, MM N 3131, Munch Museum.

18 See for example the letter to Alfred Pellegrini 1929, MM N 3328, Munch Museum.

19 Draft of a letter to Emil Schering 1898, MM N 3416, Munch Museum.

20 Draft of a letter to unknown recipient 1936, MM N 2548, Munch Museum.

21 Draft of a letter to Hans Posse 1928, MM N 3457, Munch Museum.

22 Draft of a letter to Frederick Delius 1929, MM N 2192, Munch Museum.

23 Draft of a letter to Meier-Graefe, 26 Juni 1897, MM N 2353, Munch Museum.

24 Draft of a letter to Frederick Delius 1929, MM N 2192, Munch Museum.

25 Draft of a letter to Eva Mudocci 1903, MM N 2370, Munch Museum.

26 Thanks to Henninge M. Solberg for help with this sentence.

27 Draft of a letter to Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche 1908–09, MM N 2655, Munch Museum.

28 Bøhn 1987:30.

29 Hinrich Schmidt-Henkel: “Kein Mann, der viel schrieb?” in Munch und Deutschland (exh. cat.), Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin 1995:78.

30 Draft of a letter to Max Linde 1909, MM N 2341, Munch Museum.

31 Letter to Max Linde 19 December 1902, MM PN 170, Stadtbibliothek der Hansestadt Lübeck.

Translated from Norwegian by Francesca M. Nichols