The Administration of an Artistic Career

A Few Glimpses from Edvard Munch’s Correspondence

A significant part of Munch’s writings have often been described as “literary diaries” as they provide accounts of events that he considered crucial for him as a human being and as an artist. But they are all written many years later, perhaps even with a sidelong glance at the possibility that they would one day be published. That is why in later years they have generally been viewed and treated as literary drafts; more than as actual diaries. They contain a substantial amount of biographical material and reflections on themes and motifs that also form part of his world of images, and as such are an important supplementary source that contributes to our understanding of Munch’s oeuvre.

But for one who seeks factual information, there is probably more to be found in Munch’s letters – those that were posted as well as drafts and rough copies. Although much of their content revolve around the same situations that one finds in his literary texts, they also contain information about pictures that he was working on, commissions, exhibitions and sundry information regarding the artworks. They occasionally give us a good overview of where he was staying and the people he met, which can provide convenient pegs for pinpointing the dates of paintings and graphic works, and in addition provide insight into how he administered this artistic career.

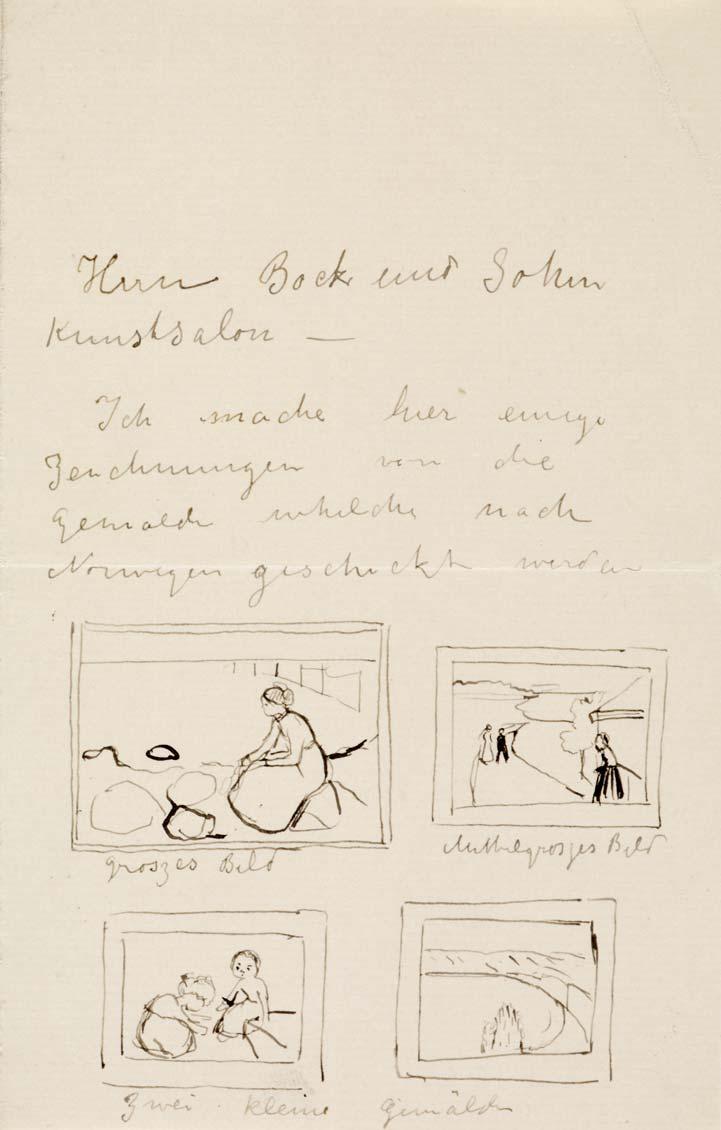

ILL. 18. LETTER FROM EDVARD MUNCH TO BOCK UND SOHN 1894, MM T 2818-1

Edvard Munch painted his first small paintings in oil as a 17 year old in the spring of 1880 and drew his last lithograph at the age of 80, only weeks before he died on 23 January 1944. In the course of these years he made approximately 2000 paintings – including loose sketches and studies – and printed approx. 30000 impressions. Munch never made lists or systematic logs of what he made – or when he made them. In addition to exhibition catalogues, reviews and photographs, his correspondence represents an important source in the work of bringing a little more order to this artistic career.

Although many of the artworks were sold or given away in the course of a long life, Munch kept a striking number himself. In his youth, when he was in desperate need of money, there was not a large market for his art and he later became more and more reluctant to relinquish works that he felt were important. After he settled down at Ekely in 1916, he collected the majority of his artworks there, and photographs and accounts from the 1920s and 30s give the impression of an almost insurmountable mess, with pictures hanging on all the walls both outdoors and indoors, as well as lying in piles scattered about on the floor. Anecdotes about the storing of apples in the grand piano and the use of prints as lids on pots while preparing food have contributed to substantiating the image of a totally impractical, eccentric artist.1 But there must have been a certain degree of order in the midst of all the mess, even though Munch complained again and again himself about how difficult it was to locate prints for exhibitions or sale. Rare, early prints were in all probability kept in a chest of their own, and the canvases and paintings that can be seen strewn on the floor in many photographs, were most likely loose sketches and drafts that had served their purpose.

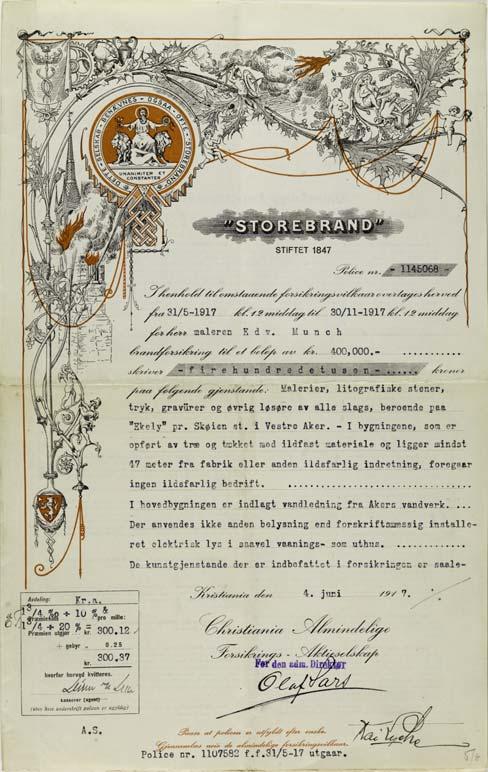

What struck me most during my work of cataloguing Munch’s graphic and painted works was not the chaos at Ekely, however, but the fact that he had managed to single-handedly administer this work during his entire life, with the exception of a very few years, 1904–08, at which time he had contracts with two art dealers regarding the sale and exhibiting of paintings and graphic art. The Munch Museum’s register of the exhibitions during Munch’s lifetime amounts to more than 500 large and small exhibitions in which his works were included. Although security around Munch exhibitions is quite different in our time, the logistics involved were very much the same. A selection had to be made, the pictures had to be found and checked to see if they were in relatively good condition. Contracts had to be drawn up for renting exhibition premises and for dividing up the income, and for insurance and transport of the works (ill. 19). Catalogues – printed or in the form of labels at the exhibition – had to be equipped with titles, dates and prices. Before Munch settled in Norway for good in 1909, the pictures were often located all over Europe. Graphic works were often held by printers or art dealers, while the paintings could be at an exhibition, or stored in studios and hotel rooms in Paris or Berlin. So even then, putting together an exhibition was like trying to put together pieces of a puzzle.

After Munch’s return to Norway, he obtained his own presses so that he could print his own graphic works, and he therefore also had to ensure that he had printing ink and the proper paper on hand. Both the presses and the equipment were mainly ordered from Germany, and during the work with the Aula decorations special orders of large canvases had to be obtained from the Netherlands. At his home in Kragerø, Skrubben, he had hired people to take care of the housekeeping and the garden, and they also had to step in when it came to sewing large canvases together or constructing the so-called open-air studios where he could mount the huge canvases he was working on. In Hvitsten, where he bought the property Nedre Ramme in 1911, he also had domestic animals that were used both as models and as food. He established a similar household at Ekely, when he bought the former market garden in 1916. In other words, in addition to his artistic activity, he also had to oversee the running of a substantially sized farm. Through countless letters and complaints to the tax authorities from the 1920s and 30s one gets an interesting glimpse of the running of this “arrangement”, as Munch called it. Not only did the authorities demand that he state the exact value of the “goods in stock” – that is, all of the artworks he had lying around – he also had to produce a balance sheet for the use of electricity, hay for the horse and the planting of cabbage. These outpourings are perhaps among the most amusing that Munch left behind, with their many cutting remarks and astute observations that may have relevance even today.2

ILL. 19. INSURANCE POLICY FOR WORKS OF ART AT EKELY 1917

As far as we know, Munch organized his very first solo exhibitions in Kristiania in 1889 and 1892 totally on his own, which is to say he rented the premises, printed the catalogue, procured electricity so that the exhibition could be held open in the evenings, and sold entrance tickets. How he organized this in a purely practical sense, we do not know, but there is reason to believe that even then he must have had a well-developed talent for getting help from friends and acquaintances, otherwise it would be almost impossible to fathom how he could have managed it. But when the 1892 exhibition travelled to Berlin that fall, where it created a sensation and was closed down after only one week, Munch’s letters reveal that the young artist was far from lacking a flair for business: “ – This is the best thing that could have happened, by the way, I could not ask for better advertising – the Art Dealer Schultze has offered me either 200 Marks cash or 1/3 of the Income when he exhibits the pictures in Cologne and Dusseldorf”.3

A few days later he regretted not having arranged himself to show the exhibition in Berlin immediately after the closing, and in addition complained about the fact that he did not earn much from the exhibition tour arranged by Schultze, since most of the earnings ended up in the art dealer’s pockets.4 This he attempted to make up for, however, by renting rooms in Equitable Palast in Berlin himself, and reopening the exhibition there around Christmas the same year.5 As an eye-catcher he had ordered a large Norwegian flag from home and hung it on the building’s façade. On this occasion he also had the exhibition photographed and a photo album made containing pictures of many of the exhibited paintings. He also had a catalogue printed – and as a whole this comprises a very important basis for identifying which works were actually included in the exhibitions of 1892–93.

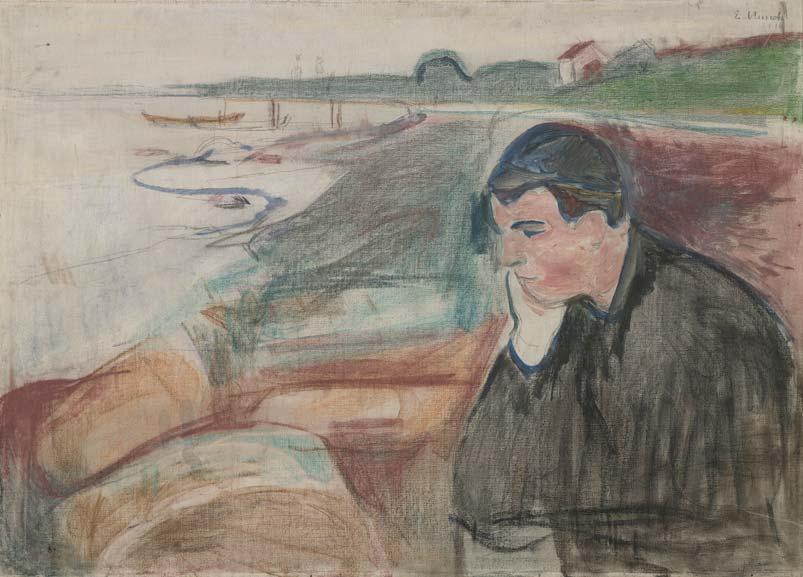

CAT. 4. EVENING. MELANCHOLY 1891

After the exhibition was shown in Equitable Palast it was sent to Copenhagen before being sent on a new tour of Germany. Munch was not present himself during the mounting in Copenhagen, but in a letter to the Danish painter Johan Rohde, it is quite evident that he had his own opinions about how the exhibition should be hung: “I would appreciate very much if these Paintings could be well placed: A young man who sits with his hand under his chin on a Beach – A sick girl – The mystery of a night – Night – Girl looking out through a window – A red sky with a young man leaning over a railing – Portrait of Hans Jæger – Portrait of Karl Jensen. The remainder I leave up to your judgement.”6

In 1894–95 Munch took up printmaking as a new artistic medium, and thus gained new opportunities for exhibitions and sales, but also much more to keep track of (ill. 20). Because he did not print editions in limited numbers, he also had to make sure that the plates and stones were kept in good condition so that he could make new prints when it was desirable. The metal plates and the wood blocks belonged to the artist, but for Munch – who was constantly travelling and did not have a permanent dwelling before he settled in Kragerø in 1909 – the most practical solution was that these plates were also stored in the printing houses. The lithographic stones, on the other hand, normally remained the printer’s property, and large and fragile as they were, they were extremely ill-suited for transporting long distances. In order to prevent the stones from being ground down Munch had to either pay rent – or buy them. In the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris there are three letters he wrote to the famous lithographer Auguste Clot regarding the rental of 23 lithographic stones.7

From Munch’s letters to the printing houses we can also ascertain that he would often order a quantity of impressions of specific motifs, often specifying what type of paper he wished to have them printed on. In order to avoid any misunderstanding about which motifs he was ordering prints of, he would sometimes make small drawings on the letter, as we can see on a draft of a letter to Clot where he requests 50 impressions of the lithographs Attraction I and On the Waves of Love (ill. 9, p. 42).8

Unsafe conditions during storage and transport led to several of Munch’s pictures being destroyed, and in such cases it was a great advantage if they were properly insured. In 1890 five paintings by Munch were destroyed in a fire in Chra. Forgyldermagazin, and the first version of The Day After was most likely among them. But the insurance sum of 700 kroner was not a bad compensation for a painter who at that time hardly sold a thing.9 In December 1901 a painting belonging to Olaf Schou was destroyed in an explosion on board a ship while returning to Norway after an exhibition in Munich, and as was the custom, Schou used the insurance money to acquire another painting from him. This gave Munch the means to rent a studio of high standard in Berlin in the beginning of 1902.

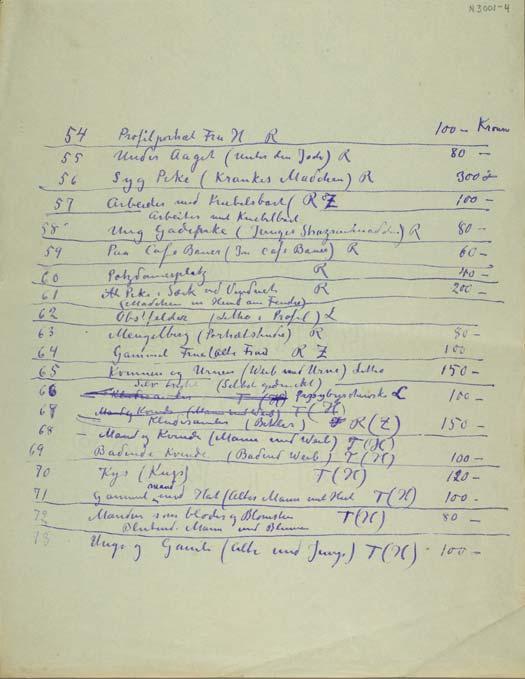

ILL. 20. EDVARD MUNCH’S INVENTORY OF GRAPHIC WORKS, C 1912, MM N 3001-4

In the course of 1902 Munch found three very important helpers in Germany, and the correspondence with them is among the most important sources of information about his art during the following years.10 The eye specialist and art collector Max Linde in Lübeck bought the painting Fertility directly from Munch in the winter of 1902, and in the fall Linde was persuaded by Albert Kollmann to buy more or less all of Munch’s engravings. The lawyer Gustav Schiefler saw these engravings by chance during a visit to study Linde’s art collection, and became so infatuated with them that he contacted Munch shortly thereafter, and already in 1904 began collecting material for a catalogue raisonné of his graphic works.11

With the help of these three men, Munch succeeded in the subsequent years in becoming established as a popular artist in Berlin. He exhibited in many places, sold quite a bit in fact, was given several commissions to paint portraits, and painted decorations for Dr. Linde and Max Reinhardt. In 1904 the growing interest in Munch’s art caused two art dealers, Commetersche Kunsthandlung in Hamburg and Bruno Cassirer in Berlin, to offer him contracts that would secure them exclusive rights for several years to the sale and showing of paintings and graphic art respectively.12 The conditions of the contracts were duly studied and commented on by both Linde and Schiefler. Munch finally signed three-year long contracts with them both, which he subsequently complained about in many letters. He did not feel that they did enough to either show or to sell his art.

Independently of Commeter – and possibly in breach of the agreement – Munch received a commission in 1905 to paint a portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche from Ernest Thiel in Stockholm, and that was the initiation of yet another important acquaintanceship. When it appeared that Munch owed Cassirer money instead of the reverse after the end of the period stipulated in the contract, it was a large commission of prints from Thiel that made it possible for Munch to extricate himself from the agreement.13

The contract with Commeter, however, entails an extremely important element. In order to keep track of the approximately 100 paintings that Munch put at his disposal, Commeter had them photographed hanging closely together on a wall and numbered them according to written lists. He sent copies of these to Munch, and with the exception of a few photographs that are missing today, they are a very important source for dating ante quem and for identification of the paintings that were shown at the exhibitions during these years. As for the prints, Schiefler’s catalogue from 1907 became an important aid for exhibitors, salespersons and collectors – at least on the Continent – but when it comes to the paintings there are no other overviews beyond the lists and photographs from Commeter. In 1909 – when the need arose for supplementing Schiefler’s catalogue of graphic works, and Munch once again concentrated on the Scandinavian market – he also had his prints photographed and small pictures pasted in an album. All of them were given a number that corresponded with written lists, and for many years the photographs and lists circulated among exhibitors and art dealers.14

One of Munch’s helpers in Norway was Sigurd Høst from Bergen. Among other things he mediated the sales to Rasmus Meyer, and in a draft of a letter Munch asks him to suggest to Meyer that if he wanted all of his graphic works – as Dr. Linde and Director Thiel had – he could have them for a reasonable sum. Munch, who was just then assembling a collection of prints for Thiel, continued with the following resigned remark: “The worst thing about selling Prints is to find them – to make them is relatively easy – so he should take advantage of the Opportunity”.15

The dating of Munch’s works is a well-known problem, and it was not always easy for those who previously arranged exhibitions of his art either. The letters therefore also contain many points of reference for the dating of the artworks. He was often hard-pressed to put dates on the works that were being exhibited, and on the exhibition lists sent from Bielefeld in 1931, for example, he has added the year on many of the paintings and prints that were not included in Schiefler’s catalogues.

Significant parts of Munch’s correspondence have already been published in their entirety. And everything has been available in transcript form in the museum’s library for decades. With the online publication of all of his texts, a new milestone will have been reached in the research on Munch. Yet what still remains is the other half of the correspondence: The letters to Munch. They are often crucial for understanding the context, and one can hope that they too will be made available in the near future.16

Notes

1 Rolf E. Stenersen in particular has contributed to this through his extremely popular book Edvard Munch. Close-up of a Genius, which has been published in many editions since 1944, when it was first published in Swedish.

2 Some of this was published in a separate catalogue booklet, Gerd Woll: Fra kunstnerens verksted. En utstilling i Munchmuseets Vestfløy, 1998. Drafts of letters to the tax authorities can be searched directly or via Johs. Roede at eMunch.no. Cf. for example MM N 143, MM N 329, MM N 565.

3 Letter Munch/Karen Bjølstad 12.11.1892. Published as letter no. 128 in Edvard Munch brev. Familien, Oslo 1949. Original in the Munch Museum: MM N 785.

4 Letters Munch/Karen Bjølstad 17.11. and 26.11.1892, published as letters nos. 129 and 130 in op.cit. Original in the Munch Museum: MM N 786 og MM N 787.

5 In a letter to Inger Munch he tells her of the result: “– the total input is 1800 Marks – from the entrance fee – but the profit unfortunately will not be high, since the expenses were frightfully large”. Letter Munch/Inger Munch 20.1.1893, letter no. 133 in op.cit, Munch Museum MM N 790.

6 Letter Munch/Johan Rohde 8.12.1893. Original in private collection, transcription in the Munch Museum, registrered as PN 20. Shortly after Munch wrote again to him: “It would interest me greatly to hear Your opinion about my pictures, which from what I have heard You were so kind as to hang up –”. In this letter he also writes that he is working on a series of paintings, in which many of the pictures that were shown at Kleis are included, and that he thinks they will be easier to understand when they are all brought together. The pictures are to be about love and death. These two letters have justifiably been attributed great importance in Munch research – as the first hint of the development of his great frieze of life project.

7 Originals in the Bibliothèque Nationale, transcripts in the Munch Museum: PN 44, 46, 47. He must have bought several of the lithographic stones later and had them transported to Lassally in Berlin, and later to Norway.

8 Undated draft of letter Munch/Auguste Clot. Original in the Munch Museum: MM N 2181. He could also do something similar to specify which paintings he wished to have sent to Norway after the close of an exhibition, for example – as is stated in an undated draft of a letter from 1894, written in the notebook MM T 2818.

9 Letter from Chra. Forgyldermagazin 5.1.1891, and a letter from Karen Bjølstad 29.1.1891, no. 96 in op.cit. where she also brings up the difficulties in having money transferred to Edvard Munch abroad. During these early years it was primarily the family who had to help out in this way.

10 The correspondence between Munch and Linde published in Gustav Lindtke: Edvard Munch – Dr. Max Linde : Briefwechsel 1902–1928, Lübeck 1974; Munch and Schiefler in Edvard Munch/Gustav Schiefler Briefwechsel, Vol. 1 1902–1914, Hamburg 1987, and Vol. 2 1915–1935/1943, Hamburg 1990. In 1985 the Munch Museum acquired Munch’s letters to Albert Kollmann, and thus has nearly the complete correspondence between them. Cf. also Lasse Jacobsen’s article on Edvard Munch’s writings after 1944.

11 Gustav Schiefler: Verzeichnis des graphischen Werks Edvard Munchs bis 1906, Berlin 1907, and Edvard Munch. Das graphische Werk 1906–1926, Berlin 1927.

12 The agreement with Commeter, including photographs and lists, is published in Munch/ Schiefler: Briefwechsel 1 and in Vol. 4 of Gerd Woll: Edvard Munch. The Complete Paintings, London 2009. The contract with Cassirer is mentioned in the introductory chapter of Gerd Woll: Edvard Munch. The Complete Graphic Works, London 2001.

13 A selection of correspondence between Munch and Ernest Thiel is published in Ulf Linde: Edvard Munch og Thielska Galleriet, Oslo 2007.

14 Cf. Gerd Woll: “Der nordische Katalog” in Munch/Schiefler: Briefwechsel 2.

15 Undated draft of a letter Munch/Sigurd Høst, c 1909–10, original in the Munch Museum (MM N 3236). Both Ernest Thiel in Stockholm and Rasmus Meyer in Bergen acquired large collections of Munch’s graphic works, which are still included in the public art collections that bear their names: Thielska Galleriet and the Rasmus Meyers Collections/Bergen Art Museum. Dr. Linde’s art collection, on the other hand, was dissolved during the 1920s.

16 Of the important correspondence that has not yet been published, the exchange of letters with Jens Thiis and with Ludvig Ravensberg can be mentioned in particular. In both cases the Munch Museum also has the original letters from Munch, which is otherwise quite rare. Both were close friends of Munch throughout a long life, and these letters include important information about his art.

Translated from Norwegian by Francesca M. Nichols